A Hybrid Approach To Oyster Reef Monitoring

With all the excitement and enthusiasm around oyster restoration in Chesapeake Bay, you may be surprised to learn how difficult it is to answer one very important scientific question: how are the oyster reefs doing?

The famously cloudy water of the Bay and the underwater lifestyle of our oysters pose a challenge for scientists who are taking on the important tasks of counting oysters and evaluating reef structure.

Current oyster reef restoration efforts in Chesapeake Bay are centered on the Chesapeake Bay Program’s work to restore reefs in 10 tributaries by 2025. Maryland and Virginia, Federal partners like NOAA and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, and nonprofits and academic institutions are teaming up for this large-scale work. One of the strengths of Chesapeake Bay oyster restoration is that scientists are making the extra effort to collect monitoring data to assess whether restoration has succeeded. The metrics of success include increasing oyster populations and restoring vertical reef habitat and show that this work has been very successful in helping bring back oyster reefs.

However, monitoring oyster reefs is difficult because existing methods rely on physical sampling of oysters using fishing gear or divers as well as extensive sonar surveys.

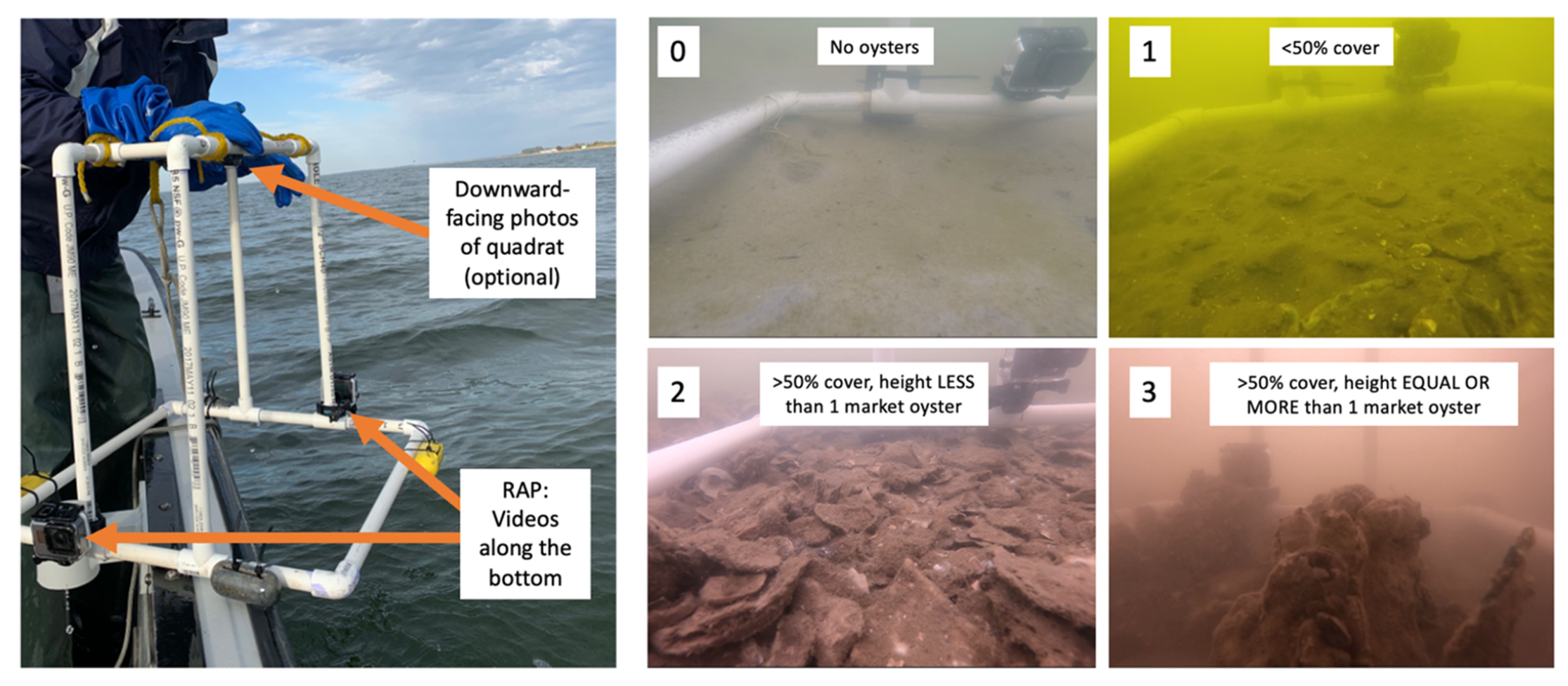

Dr. Allison Tracy (UMBC/ UMB-IMET) and co-authors at the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center (SERC) tackled this problem in a recent study, published in Restoration Ecology. Their field study compared oyster reef metrics using existing methods to a SERC-developed Rapid Assessment Protocol (RAP), which relies on remotely collected underwater imagery.

Tracy and her colleagues traveled up and down the Chesapeake Bay to compare oyster density, biomass, and other physical metrics from diver-collected samples with a habitat score derived from the RAP’s underwater imagery. Divers first deployed the RAP frame to record images of a patch of oyster reef, after which they excavated that precise patch of reef by hand to count and measure every oyster. They analyzed this comparison for 64 patches in high, medium, and low salinity regions of the Bay.

Overall, the study’s authors found that the RAP method successfully captured high performing reefs. The highest RAP scores of 3 (see image) had high live oyster densities, high live oyster biomass, greater reef height, greater rugosity, and a broader range of oyster sizes. Moreover, estimates of the time required for the RAP and existing methods showed that the RAP is more efficient. Tracy says of the work: “Strategically combining the strengths of the RAP and existing monitoring methods in a kind of hybrid approach could help save time and money while still providing the information managers need.”

The authors consider the results to be promising for improved monitoring methods in Chesapeake Bay, but they also hope that this work can be integrated into the state-of-the-art for benthic monitoring worldwide.

This project was funded by the NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office (Award NA21NMF0080474).