IMET International Collaborations: Vietnam

A solution to a supply-and- demand problem that starts in Vietnamese homes might be floating in the country’s coral reefs, mangrove forests, and seagrass sanctuaries.

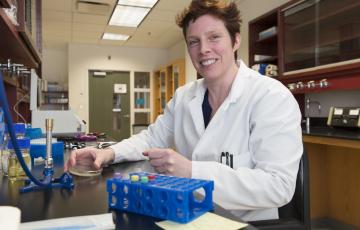

In Vietnam, cooking oil is a common ingredient that comes at a high cost because more than 90 percent of it must be imported from countries such as the United States, but scientists, including the Institute of Marine and Environmental Science Director Russell Hill, are seeking a more affordable alternative in microalgae.

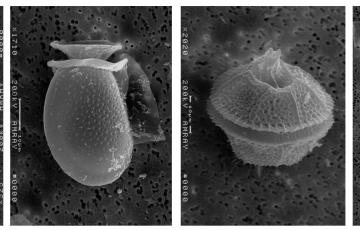

These miniature plant-like species are plentiful, growing in a variety of bodies of water, and diverse, including some with high oil yields. Other good traits are high photosynthetic efficiency and fast growth rate. Microalgae have already shown potential as a source for alternative fuels, which is just one research area for Hill and his IMET colleagues.

“They don’t have the lands to grow crops like soy that are grown all over the US and provide most of our cooking oil,” Hill said, adding, “They can pick the one or two best microalgae and then they can start scaling them up.”

Before they could identify the best microalgae to grow for larger distribution, they needed to isolate many strains from the water samples they collected. That’s where Hill came into the project.

In 2012, scientist Yen Thao Tran with the Research Institute for Oil and Oil Plants in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam was visiting the United States and set up a meeting with Hill. Her group is proficient in working with oils and she called on Hill for his expertise in isolating the microalgae. The scientists then crafted a proposal to the Vietnamese government, and earned funding to get the project going and cover Hill’s travel expenses. Hill traveled to Vietnam four times for the project between 2013 and 2016, and the research paper, “Isolation and Selection of Microalgal Strains from Natural Water Sources in Viet Nam with Potential for Edible Oil Production,” published in Marine Drugs on June 23, 2017.

Work started in various regions of the country. The team of scientists collectively pulled water samples from lakes, rivers, and other bodies of water across 15 provinces in Vietnam. As Hill helped retrieve samples from Ha Long Bay on Vietnam’s northern coast, he enjoyed the landscapes of a country he never previously visited.

“I loved those trips because I got to travel around different parts of Vietnam to actually take water samples myself and then I worked in the lab, which I hardly ever do when I’m here,” he said, sitting in his director’s office at IMET.

Hill also enjoyed working with the Vietnamese scientists and technicians in their lab, where they started the process of growing the microalgae in those water samples.

“They grow in light and if you put them in the right medium without any added carbon, they can photosynthensize, and they grow well and can be isolated,” Hill explained.

They turn green or pink or other hues signaling it is time for the scientists to slowly purify them and then leave them to grow again.

To see if any of the microscopic species hold oil, the scientists stain them and look for small orange droplets.

“That tells you that you have a strain with oil and then you can start scaling up and growing more of the algae, and you actually extract the oil, measure it, and purify it,” Hill said.

Twenty of the 50 strains that the scientists isolated had strong growth rates, produced high biomass, and had high lipid content.

By the end of this study, several were selected for further analysis. This effort was just the first step of the process to determine if these algae could be sources of oil for cooking oil, Hill said.

The research opportunity was also a potential first step toward more collaborations.

“Now we have a good productive collaboration in place and we can demonstrate that we actually succeeded in doing some things together,” Hill said. “Hopefully this will lead to some new opportunities down the road.”